Bekijk de songtekst Breng Me Naar Het Water van Marco Borsato op Songteksten.net

— Read on songteksten.net/

Songteksten.net – Songtekst: Claudia de Breij – Mag Ik Dan Bij Jou?

Als de oorlog komt,

En als ik dan moet schuilen,

Mag ik dan bij jou?

Als er een clubje komt,

Waar ik niet bij wil horen,

Mag ik dan bij jou?

Als er een regel komt

Waar ik niet aan voldoen kan

Mag ik dan bij jou?

En als ik iets moet zijn,

Wat ik nooit geweest ben,

Mag ik dan bij jou?Mag ik dan bij jou schuilen,

Als het nergens anders kan?

En als ik moet huilen,

Droog jij m’n tranen dan?

Want als ik bij jou mag,

Mag jij altijd bij mij.

Kom wanneer je wilt,

Ik hou een kamer voor je vrij.Als het onweer komt,

En als ik dan bang ben,

Mag ik dan bij jou?

Als de avond valt,

En ‘t is mij te donker,

Mag ik dan bij jou?

Als de lente komt,

En als ik dan verliefd ben

Mag ik dan bij jou?

Als de liefde komt,

En ik weet het zeker,

Mag ik dan bij jou? Mag ik dan bij jou schuilen,

Als het nergens anders kan?

En als ik moet huilen,

Droog jij m’n tranen dan?

Want als ik bij jou mag,

Mag jij altijd bij mij.

Kom wanneer je wilt,

Ik hou een kamer voor je vrijMag ik dan bij jou schuilen,

Als het nergens anders kan?

En als ik moet huilen

Droog jij m’n tranen dan?

Want als ik bij jou mag,

Mag jij altijd bij mij

Kom wanneer je wilt,

‘k hou een kamer voor je vrij.Als het einde komt,

En als ik dan bang ben,

Mag ik dan bij jou?

Als het einde komt,

En als ik dan alleen ben,

Mag ik dan bij jou?

— Read on songteksten.net/

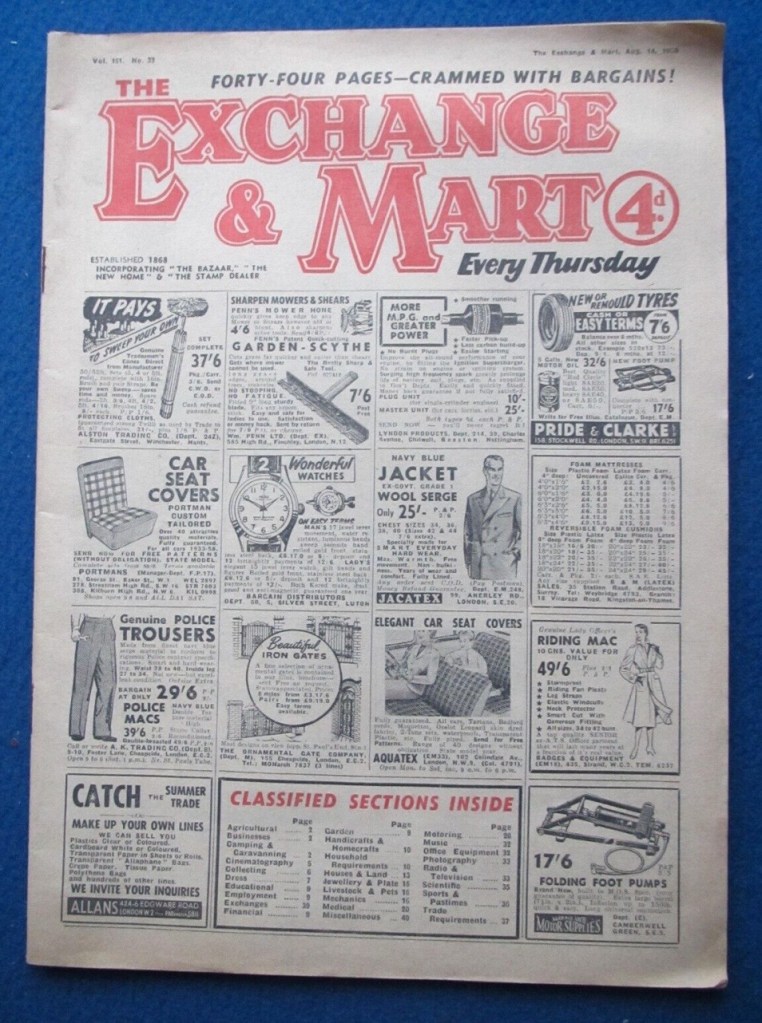

Exchange & Mart

Having just stumbled on the Dutch term “de ruilbeurs” (exchange mart) whilst reading Dimitri Verhulst’s thoroughly engaging “De helaasheid der dingen”, I find myself reminded of the publication “Exchange & Mart“, which was often a source of fascination during our childhood, as indeed were the various stores of the same name.

The great philosophers

La grande bouffe – Old Yorker

La grande bouffe – Old Yorker

— Read on oldyorkeronline.com/la-grande-bouffe/

Judith Butler’s toxic nonsense – UnHerd

Her mastery of claptrap would be hilarious if it weren’t so dangerous

— Read on unherd.com/2021/09/judith-butlers-toxic-nonsense/

An excellent piece on the empress of eyewash. LJ

Peter Falk, as Columbo

Having watched one or two episodes of Columbo recently, I wondered whether Peter Falk had actually smoked cigars himself. In response, I found this obliging article.

Another instance to stimulate consideration of the Sorites paradox.

Giles Udy discusses the ideology behind the gulags.

Grelling’s paradox of heterologicality

This paradox turns on the definition of the opposition between its the sense of “heterological”, referring to words that do not instantiate their own meaning, and that of “autological” or “homological”, referring to terms that do instantiate their own meaning. Examples typically cited are “short” and “polysyllabic”, which, since they instantiate their own meaning, are autological or homological, in opposition to “long” and “monosyllabic”, which do not do so and are therefore heterological. The paradox resides in the meaning of heterological, and is related to the barber paradox et al.

Initially, I could think of no other examples of terms thus instantiating their own sense, until recently, when, whilst frivolously composing limericks, I gave some thought to the terms defining metrical feet. Most of these are heterological, but “trochee” instantiates its own meaning and is therefore autological.

It has just occurred to me that « antonym » is also heterological.

Just a thought. I’m still looking for other examples, but not diligently! LJ

You must be logged in to post a comment.